Why Is Brand Architecture So Hard? (and How to Make it Easier)

A quick definition: Brand architecture refers to the organised structure that defines how a company’s various brands, sub-brands, products, and services relate to each other. It acts as a framework to manage a brand portfolio and clearly communicate the relationships between different offerings to customers.

Why it matters: A strong brand architecture provides structure and clarity both internally and externally, locking in loyal customers and attracting new ones. It also acts as a strategic tool to guide future brand development and expansion decisions.

So why is it so very hard to create the right brand architecture?

It’s hard because defining a brand architecture doesn’t come along often in a marketer’s career, so people don’t have much experience or a trusted process to follow. If you’re in a large company, a big brand architecture project may only happen every 5-10 years, and if you miss it, you’re unlucky. It often leads to a case of imposter syndrome, where you feel like you ought to know what to do, but you don’t.

It’s double hard because it requires a bird’s eye view across the totality of the brand. If we’re talking about a big brand, few people within the brand organisation have a deep understanding of all the parts and pieces.

It’s triple hard because you need to view the brand through the eyes of external audiences rather than internal perspectives and biases. It’s remarkable how often people believe that their internal organisation chart correlates to how outsiders perceive their brand.

It’s quadruple hard because you need to think about not just where the brand is today, but where it’s going, and build in room for growth and innovation.

And it’s quintuple hard because there’s no way to quantify the right answer. Marketers love to have a number to give them confidence they’ve chosen the right direction, but there’s no way to research your brand architecture. You just have to create and evaluate the possible options and pick the best one through informed judgment.

20+ years in, with many brand architecture projects under our belt, we relish these projects with a high degree of difficulty, like the Saturday crossword puzzle. That’s because what we see, time and time again, is that a brand architecture project done right is energising and exciting for brand teams, illuminating possibilities and amplifying growth through inspiration, clarity and alignment.

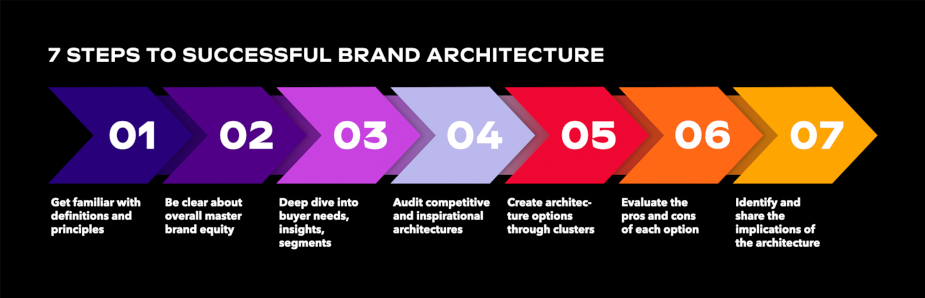

Through studying approaches and case studies, proven through our own experience of iterating the process, we have identified the 7 steps to a successful outcome.

1. Get comfortable with brand architecture definitions and principles.

Your team can’t make progress if you don’t share a common language.

Brand Architecture Principles:

Fewer brands allow for greater focus, efficiency and impact. Avoid developing a new brand should only be created when a substantial opportunity exists that cannot be reached with your existing brand.

View your brand through the eyes of who your core brand appeals to and what adjacent groups have the potential to deliver growth. Avoid the pitfalls of internal perspectives.

Keep things simple and intuitive and organise around how people think and act.

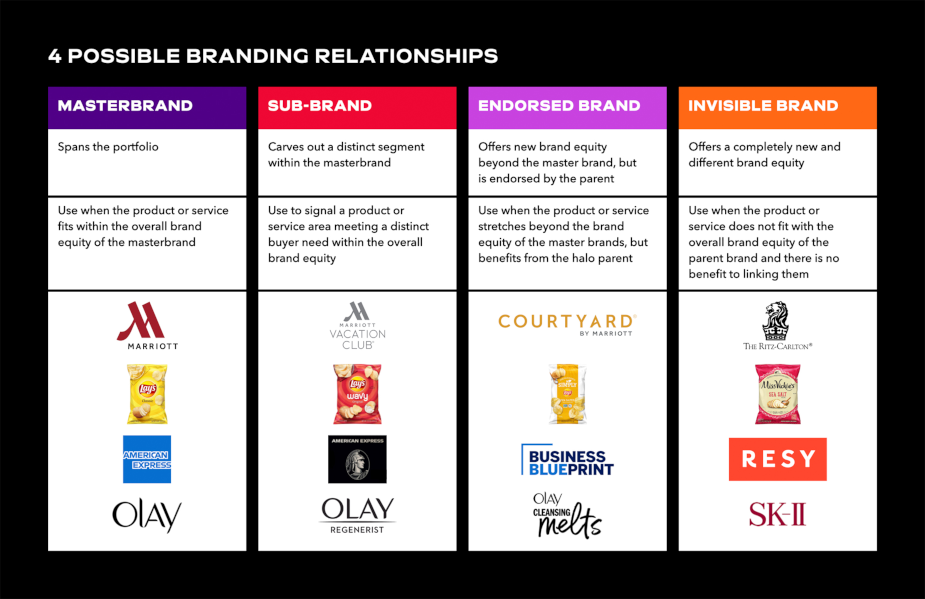

Recognise the four possible branding relationships to determine when and why to use each one: the Master Brand, Sub-Brand, Endorsed Brand, and Invisible Brand.

2. Start with clarity about the overall masterbrand equity.

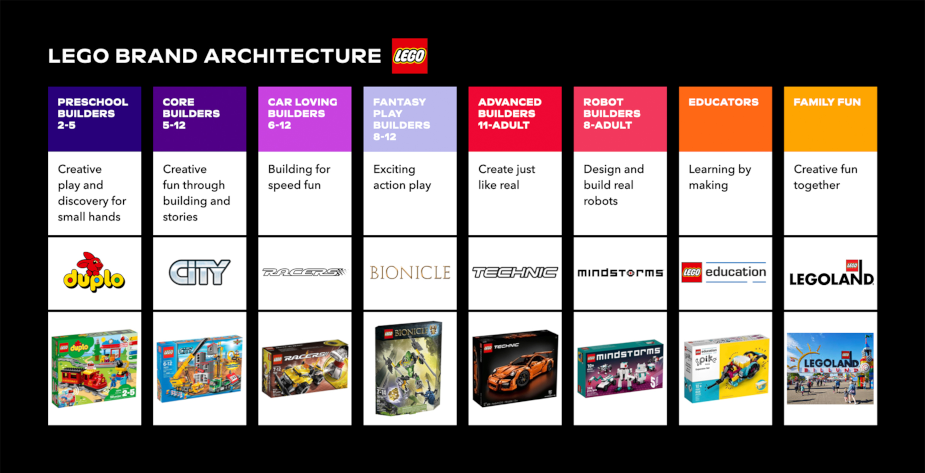

You can’t create a brand architecture without agreement on what the masterbrand stands for. If it hasn’t been well defined or there’s disagreement, it’s a must-fix-now situation to address. For example, the overall brand equity for Pepperidge Farm is to make every day feel special with fresh-baked from the farm taste, an elevated experience that earns premium prices. Lego brand equity is about the joy of building and the pride of creation.

3. Take a deep dive into current and prospective buyer needs, insights, and perceptions,

so your work is firmly rooted in the external perspective. A segmentation study to define the needs of different buyer groups is incredibly useful, but if it’s not available, tap into any other sources of consumer insight from your social media to your salespeople.

A big global brand like Lego has reams of proprietary research about the needs and desires of different age groups from two to adults. A more entrepreneurial brand like S’well relies more on publicly available data, along with insights of their team and requests from retailers.

4. Audit competitive and inspirational brand architectures

to understand what your prospective buyers are seeing about the category. How are competitors organising their brand portfolio and making it easy to shop? What’s working well? What opportunities do you see? Unlike positioning or visual identity, your brand architecture doesn’t have to be highly differentiated from competition. Work with what people intuitively know.

For Sabra, for example, we looked at hummus competitors like Cedar’s and Boar’s Head, as well as other category leader food brands, like Chobani and Philadephia, for inspiration.

5. Create architecture options for your brand portfolio through clusters that identify:

a) Who it’s for?

b) What need is it meeting?

c) What’s the main benefit for this cluster?

Your goal is to make it easy for buyers to shop your brand, so you want it to be highly intuitive.

For Lego, for example, there are natural stages and play patterns that children go through, so it is intuitive for parents to shop by age from Preschool through Elementary, High School and Adult builders, along with special interests like car lovers, fantasy play, and robotics.

6. Evaluate and debate the pros and cons of each option.

Is it highly intuitive for buyers?

Does it elevate and reinforce the masterbrand?

Does it build in room for growth?

Make a strategic decision as a team on the best option and optimise it.

Pro Tips:

- Unless you’re one of the biggest brands in the world, you probably don’t need more than three or four clusters;

- It’s totally OK and expected to have outlier clusters that are different from the pattern of the others.

This is the moment marketers wonder “can I test this and quantify the right answer?”The answer is no. In order to test an architecture, you would need to bring it to life and that is prohibitively expensive to do for multiple options. And the whole point is to create different pillars for different buyer segments, so it’s practically impossible for any respondent to give you useful feedback.

Get comfortable with debating the options and reach your conclusion together. This debate and alignment is critical for unifying and energising your team to act on and be inspired by the chosen architecture.

With Hyatt’s example below, there is a tiering strategy from Luxury to Mid-Scale that reflects the fact that price is a primary consideration for travellers. Within each tier, however, there are options to appeal to the guest persona from luxury connoisseurs to discovery mavens to work/life balance seekers.

7. Identify and share the implications of the brand architecture.

Is there a need for a transition strategy from today to the new architecture?

How should each cluster be expressed visually and verbally?

What is the relationship of each cluster to the masterbrand? What does it mean for innovation strategy?

So, is brand architecture challenging? It sure is.

But a solid brand architecture delivers a roadmap of clarity that cuts through the chaos of daily demands.

Stepping into it bravely with a clear process helps you reduce imposter syndrome and increase team engagement and enthusiasm.