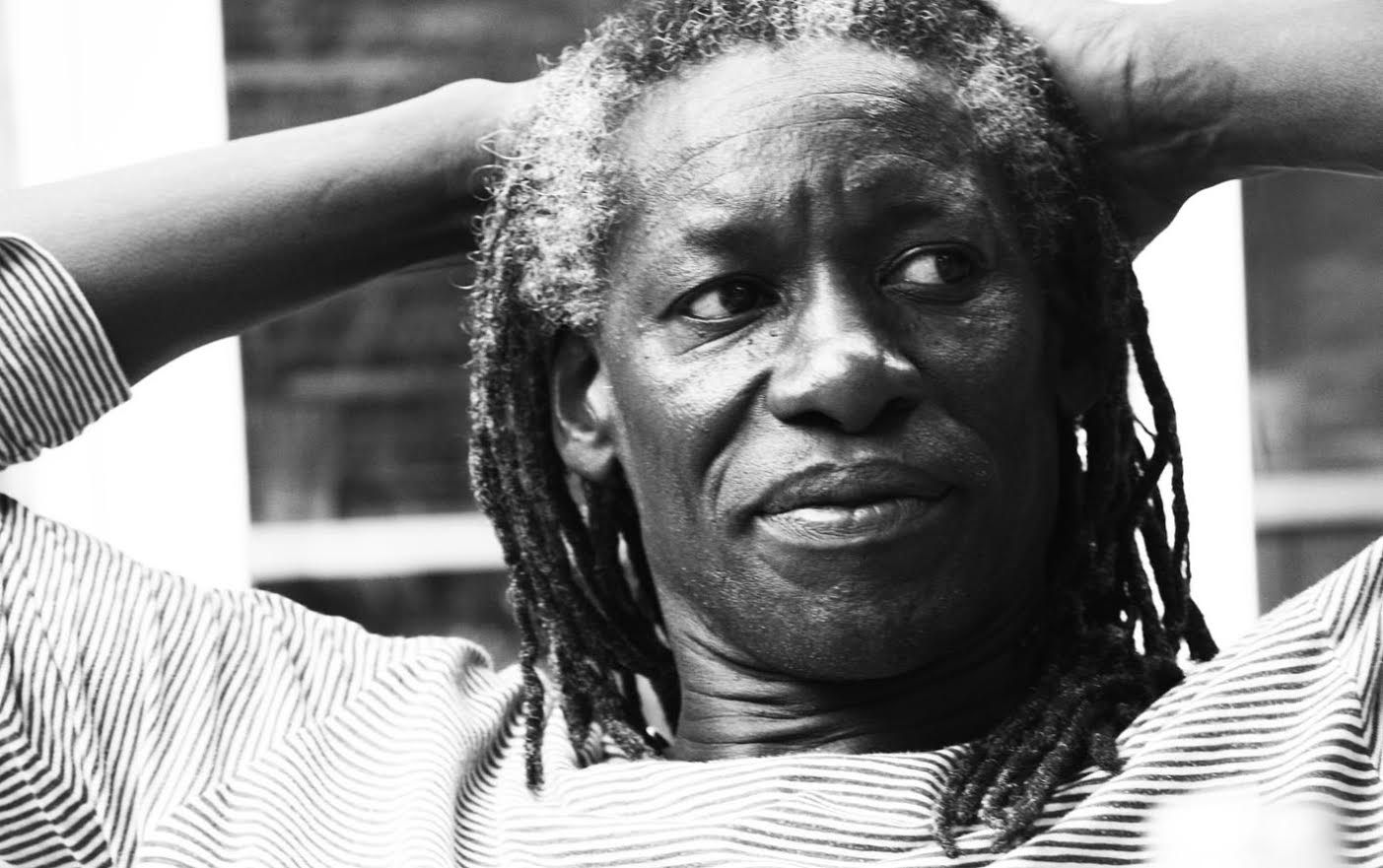

5 Minutes with… Trevor Robinson

When Trevor Robinson opened the doors of Quiet Storm in 1995, his dream was to build a home where he could come up with creative ideas and then direct them too. It was a fairly unusual set up at the time – usually when successful creatives go off to become directors, they ditch their agency roots. But in an age of increasing fluidity, where agencies and production companies are standing on each others’ toes, Trevor’s hybrid idea has proven remarkably prescient.

He first caught the directing bug back when he was working at the legendary London hotshop Howell Henry Chaldecott Lury. With his creative partner, Al Young, he’d attained notoriety with the 1992 ‘Orange Man’ Tango ad, which led to gleeful copycat slapping in playgrounds up and down the UK and kicked off the long running ‘You Know When You’ve Been Tango’d’ platform. When it came to a follow up Apple Tango ad – a wicked piece of gleeful perversion – Trevor decided that he was going to shoot it – and he never looked back.

He’s a big character in the London advertising scene (not everyone gets an OBE from the Queen, after all), but the agency’s highest profile work for long-running client Haribo has been transposed to Sweden, Denmark and the US, making it a truly international idea.

Trevor’s also been involved in the uphill struggle to open up the industry to more diverse and interesting voices. In 2007 he launched Create Not Hate, which aimed to give kids affected by gang-related violence in London some exposure to the creative industries. While things are still slow to change, he reckons he has noticed a significant change in the way the industry is approaching diversity – i.e. less patronising hand-wringing and more recognition of the creative and business benefits of working with a broad range of people.

LBB’s Laura Swinton caught up with Trevor to find out more…

LBB> How did you get into advertising? Was it something you had wanted to do from a young age, something you discovered by accident?

TR> When I was at college I mainly thought I was going to be an illustrator or designer or something, I didn’t really know what I was going to do. I ended up at Hounslow College, which was a really famous advertising college. I used to think ‘I don’t know how you can possibly do a job where you’re having to be consistently creative all the time. I thought I would be an illustrator and I did as much freelance illustration and design work as I could at college. I was a court artist – I did the Jeffrey Archer trial!

When I came out of college I had two options – to get a job as an animator or go to a small below-the-line agency that did a bit of advertising. It wasn’t really advertising, it was stuff for pile cream and brochures. Very glamorous! It was quite depressing, because a lot of the guys that were there were at the end of their career and were quite cynical.

I met Al Young there. I had been bitten by the bug of advertising; when you start seeing the great things people are doing out there, you just want to be like them. I had started working with Tom Carty and Walter Campbell. They were at Dorland’s at the time. Tom was a post boy and Walter had managed to get a job within the agency. We’d work during the day and at night we’d meet up and work on our portfolios to try and get a job at the West End. At that point, Tom was really our Captain Ahab. He was so angry about the crap that people were doing in advertising. He was very single minded and it paid off for him.

I eventually got a job at TBWA. Tom and Walter really bludgeoned Murray Partridge into giving us a job. We were there for a two week placement and they were about to lose the Evian account, and me and Al did a piece of work that kept the account. Tom and Walter said, ‘you’ve got to give them a job’. I don’t think he liked us very much.

LBB> It’s really cool that you had that tight group that supported each other…

TR> Yeah, and we were all very different. Tom had a network of people who would come to him, even when he was a junior creative, to share their work. He was a harsh taskmaster. I remember once he appeared to me in the toilet… he said, “What do you want to do in advertising?” I said, “I don’t know, I want to make work that I’m proud of and that people remember me for.” And he just turned to me and said, “You haven’t done it yet, though, have ya?” But that was his ‘tough love’ way of saying you’re either very famous and do famous work or you shouldn’t be in the industry.

I always felt like I was on borrowed time in advertising, like any minute someone could break down the door and say, ‘we’ve just discovered that you’re here, we want you to leave’. I always felt uncomfortable so I always pushed to do work that would make it harder for someone to fire me.

LBB> And talking of that hunger, I love the story about you gate crashing industry parties to get meetings and show your work – how did that go down? And do you see much of that sort of thing among aspiring creatives trying to break into the industry these days?

TR> When we were on the dole again, there were all these creatives boasting about these breakfast parties and lunches. Me and Al used to use it as an opportunity to meet people and get them to look at our portfolios. Neither us are the kind of guys who can just slide up to people and schmooze them. We knew we had to do it but at the same time it was quite an embarrassing, painful process.

At one of these events I went up to Dave Buonaguidi, now at Crispin Porter + Bogusky. He said if he liked the work he would show it to Steven and Axel [of Howell Henry Chaldecott Lury]. He was a man of his word and I’m eternally grateful..

At the time Howell Henry was *the* agency. We would have taken a job anywhere, but we ended up at the hottest agency. Our creative directors used to say ‘they’re clambering at the doors to take your desks’. It was quite an intimidating place to go to. But good.

LBB> So does that make you sympathetic when you get pestered by hungry young creatives?

TR> I find it hard because, like most people, I’m full of my own endeavours and I’m just as impatient as anyone else when people are harassing me and sending me fake emails. But at the same time, I get it. I know how difficult it is to get a job in advertising and also to deliver your best work.

Your portfolio is not always reflective of how good you could possibly be. Some people will always create gold, wherever they go, but other people need to be in the right situation. There’s an analogy between football and advertising in that there are certain styles that just work in certain places.

LBB> What advice do you wish you’d had when you started out?

TR> It was something we eventually learned. After a year on the dole we were doing work to fit every agency. For example, Ogilvy had a really strong style – straight headline, slightly wacky image. We started to make things in our portfolio to fit their styles.

We went to see Graham Fink. He was in this massive dark room, sitting there in a big coat. He looked at our book and moaned each time he turned the page. He seemed appalled by what we had done. But he said the truest thing to us – and after that we changed our portfolio and managed to get a job at Howell Henry – he said: “Stop trying to do ads for advertising people. Start doing ads that make you laugh and ads that you want your mates to enjoy.”

LBB> Well talking of ads made to make your mates laugh… I have to ask you about your infamous Tango ad! We used to copy the slap in the playground at school and it drove our teachers mental! Why do you think Tango caught fire and became such a part of British pop culture?

TR> I was terrified that we would get fired so I knew we had to do something big to make it harder to fire us. I realised this is either going to kill us and we’d never get another job in advertising because we’d made this abortion of an ad, or it was going to make us quite famous. I didn’t think it would win awards but I knew it wouldn’t go unnoticed.

I remember being on the Tube on my way to visit my ex-girlfriend; I was half asleep and I woke to the sound of these kids raving about it. I thought they were talking to me and it turned out they were just having a conversation about it. I wanted to say, ‘I did that’ but I knew they’d think I was insane. This tramp-like guy on the train waking up and joining their conversation!

But I didn’t think people would be slapping each other!

I think it was due to the client as well. He said, ‘I want to make Coke scared’. He wanted Tango to have a British sense of humour, with British sensibilities, that didn’t feel like an ad at all. When brands really do have a tone of voice, it goes right the way through it. Tango ended up having quite an anarchic, irreverent feel that ended up affecting a lot of things that came out of it. We wanted to surprise people, not necessarily to entertain them in the traditional way. The clients bought into that, which was amazing.

LBB> Aside from the infamous slap, what’s your favourite Tango spot?

TR> It did get some awards – the Apple Tango spot. That and Pot Noodle was when Al and I started directing our own work, so it was terrifying. Apple Tango started off as a gag. One person who we worked with – who will remain anonymous – used to stay at home and pretend he was ill and get up to things… with himself. And we used to always joke that his wife was going to come back and catch him.

We decided to use that as a main theme for Apple Tango. In it, there’s a man watching a video with the Apple Tango talking seductively to him. He’s dressed up in some weird gimpy outfit. This ad still makes me laugh. I don’t know if it’s because I remember the original stories behind it. Our bosses bought into it, our client bought into it but it’s essentially about having a wank at home! It’s one of those things that shouldn’t have worked for a lot of reasons, but did and got a lot of notoriety.

LBB> In 1995 you founded Quiet Storm, which was ahead of its time as a hybrid production company and agency – why did you initially decide to work in this hybrid model?

TR> I love film, I love shorts, I love promos. The idea of directing my own work was incredibly exciting. I wanted to write and direct my own work. A lot of people went on to become directors but they stopped being creatives. People like Frank Budgen, a genius creative, stopped being a creative and became a genius director. Tom Carty as well. And I just thought, I can’t understand it.

There’s a lot of creatives who used to want to write and direct but now people want to put themselves into a box. It’s such a wasted opportunity and a waste of fun. It’s scary because you can fail. There’s nowhere to hide. You can’t blame the director! But I think when you get it right it’s so pleasing because you can escalate your own idea.

LBB> With Haribo, a long-standing client of many years, you’ve obviously a deep relationship with them and they trust you, but more generally are clients open to your way of working? Or are they quite used to the traditional model and therefore a bit wary?

TR> I used to think that would be a problem in the beginning. I was always up front, saying that our creatives also direct but they also have the option of working with other directors around the world, if that’s what they want or the project demands it. But it’s weird, a lot of clients see our reel, see that we’ve written and directed and they kind of like it. I think they like that they’re not going to be subbed off in the corner with some swanky director whose got his vision for their brand. They know they’ve been with us through the whole process, from original brief to casting to editing. They’re with us all the way.

The number of times we’ve been on a shoot and the crew don’t know who are the agency people and who are the clients! I’ve even seen crews getting clients to lug things around! And the clients love it because they feel like they are part of the process and that’s what they say matters.

LBB> So, talking of Haribo, that work has really been successful. The idea of adults talking like kids has been transposed to other markets and it’s recently gone to the States. What’s it been like to see the idea interact with other cultures?

TR> For us it’s a new experience. The campaign has always been Britain-centric, but it’s gone to Holland, Denmark, France, Spain. It’s weird to see as well because each one has the personality of the kids you interview. Everyone is the same but different. It was fascinating to see the sensibility of Swedish kids who are, before they eat the sweets, like quite uptight grown ups. You say, “what comes to mind when you see a Haribo?” And they go, “What do you mean ‘comes to mind? It’s a sweet. You put it in your mouth.” But when they start eating and interacting all this stuff comes out – and some of the most surreal stuff came from the Swedish kids in the end!

The Americans are terrifying because they’re almost like little adults. In one of the lines a kid goes ‘I’ve been busting my hump all day’ and you think, who talks like that?! They get the idea really quickly and they sound ad-y, they sound like we’ve given them words, because they’re so used to ads and consumerism already.

LBB> You're chair of the IPA Ethnic Diversity Forum – has the industry made any substantive progress, or are things going backwards?

TR> It’s difficult. When I did the diversity thing with the IPA a few years ago we spent a lot of time sitting round a big table, patting ourselves on the back. I soon realised that nothing was really going to happen. That’s when I decided I wanted to take a bit of money that I had at the bank to try and set up a project with kids from my old school. I wanted to get as many people as I could from my area into advertising because I know how many gifted and bright people are out there. They would change the face of advertising, given the opportunity and the knowledge that they can do it. They don’t even know about our industry. They don’t know they can make a career in so many different aspects.

Creative Circle has now invited me to be part of their foundation. Their thing feels like it’s going somewhere, feels like there are excited people who want to change things. They are doing this radical thing with a college for kids that don’t have cash. And it’s funded by the industry and they’re a charity. Let’s talk in five years’ time, but on paper it feels like it’s going to do something.

It also feels like the industry gets it now. Rather than everyone going, ‘we must do something because of these poor people out there’, now people say, ‘you know what, it’s good to have a female point of view, it’s good to have someone who’s like the target audience, it’s good to have the input from people from an ethnic minority background’.

Clients have been trying to drop diverse people from casting for years…and now they’re asking me to put them in. So times are changing.

LBB> Oh really?

TR> Who are we doing this work for? We’re in an industry that should be populist and should reflect the target audience and yet there’s no one who does that. It is changing but… y’know. I remember when I first came into advertising, meeting a couple of people in the hall at some award do and I remember thinking, ‘wow, a couple of black people’. And I also thought ‘maybe this means things are going to change’. And looking back, it hasn’t changed. It hasn’t progressed and moved on, and that’s insane. Every industry from music to sport has moved on – I’m not saying massively, in football a gay guy can’t even say he’s gay – but it’s moving in the right direction and people are making the right noises about racism. But to not reflect your target audience and society is dangerous. You’re limiting yourself.

LBB> I get the impression that back in the day it was the sort of industry that attracted misfits whereas maybe now things are more corporate and restrictive in that way.

TR> Definitely! Our old agency was like that, Howell Henry. They were the misfits, a maverick company. I think it’s the nature of the industry now, all the small agencies are being bought up by big… it’s becoming more and more bland, a machine. When I got into advertising, I realised that it was actually quite exciting, but now it’s becoming what I used to hate and fear, It’s all about the buck and not making mistakes and dumbing everything down.

LBB> And looking forward to the rest of the year, what have you got planned?

TR> We have a new Yakult campaign that we’ve just got signed off, got a new campaign coming out for Haribo that we’ve started working on. We’re getting the responses in from the recent Pukka Pie relaunch campaign and we’re working on some pitches that I can’t talk about yet. It’s always really exciting when you win a pitch and you get to do it, first time working with a new client. And we’re getting a new digital guy in and we’re looking for new creative teams who want to write and direct, I’m looking at portfolios now. It’s harder than you think to get people in that headspace. It’s not a traditional agency set up and the challenges are different.

It’s a very exciting time, new people coming in, new clients. We’re trying to control our size, right now it’s fun and we’re working with good people, and I’m jumping out of bed rather than dreading the day, which I used to do!