Remember When Ads Cared About Experts? I Miss Those Days

Remember when ads appealed to expertise? "Nine out of ten dentists recommend CalciDent."

It was an ad, and most likely bullshit, but at least it gestured to a world where mouth experts existed, even fussy ones: presumably that renegade tenth dentist is still out there hunting down a paste that meets their insufferable standards.

The conceptual landscape of advertising reflected back that there were people who knew more than others. This hierarchy underpinned simply social etiquette, like why passengers are not allowed to take turns flying the plane, otherwise it just becomes a missile with toilets.

In 2025, judging by the ads I’m being served, our love for experts is long gone. Now we hunt for truths from people just like us, in UGC-style moments and clips from a podcast conversation. Ads have leapt on this UGC trend: "Just trying this new protein powder", "Just discovered this AI productivity hack". Endless “real people” pretending to stumble on things they have been paid to promote.

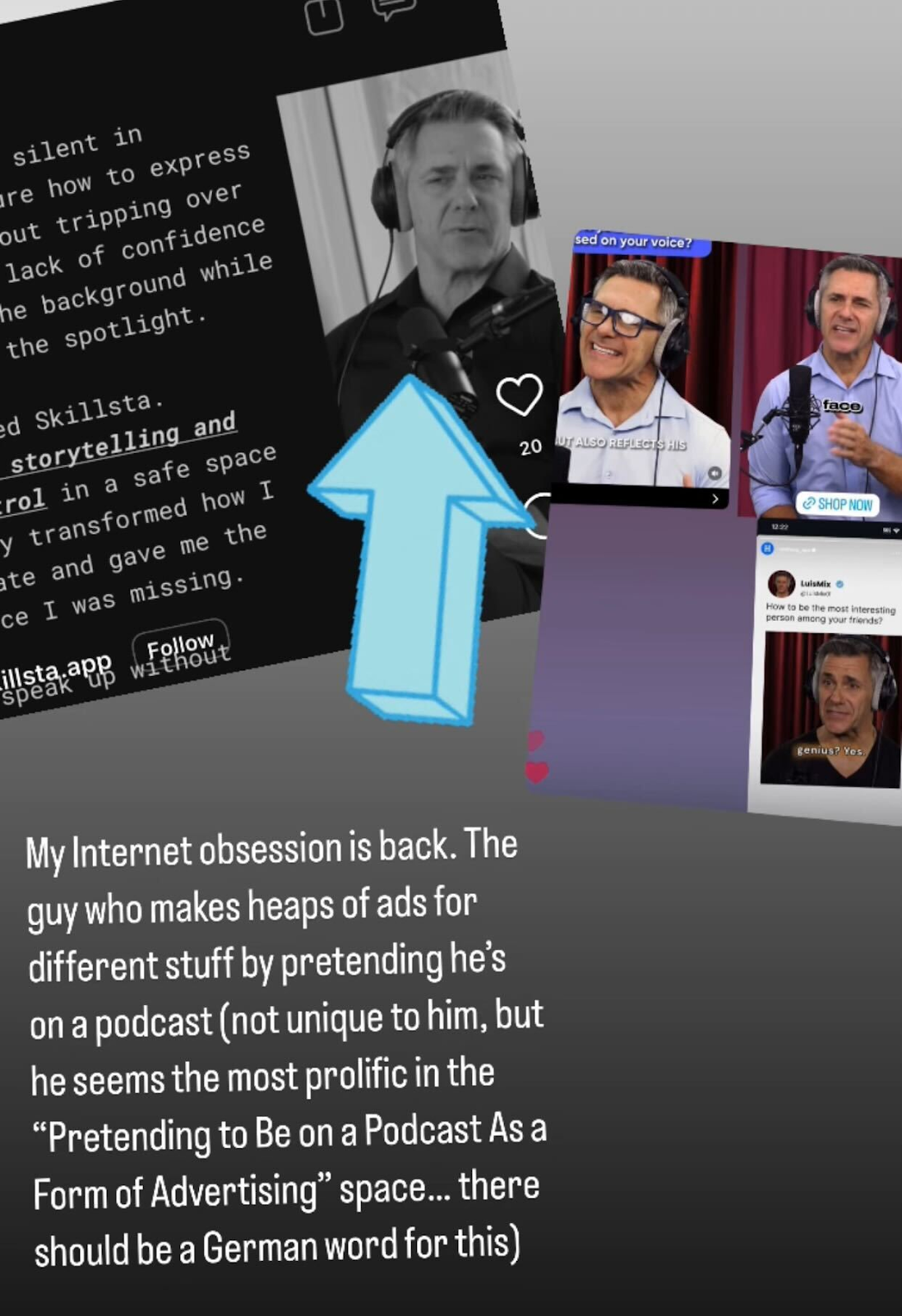

My biggest peeve is the faked conversation snippet from a podcast that does not exist. "How did I reverse my age? Well, thank you for asking." (Who are you talking to?) "For my language learning, this new AI app was game-changing for me." (Who?)

It is a new sub-branch of the enshittification of the internet: endless ads with people looking just off-camera, talking to an imagined host. But the performances -- more wooden than John Wayne after a botox overdose -- can’t mask the fact no one else is there. These people are often talking to a non-existent co-conversee.

Health, spirituality, singing apps, language learning, whatever your algorithm susses out, you will find someone pretending to chat about it. Now, with AI video generators like Veo, expect a tsunami of never-happened, photorealistic conversations tailored exactly to your (commodifiable) interests.

So what does this say about our relationship with expertise and truth? Nothing good, nothing new, nothing surprising. Andrew Keen’s prescient 'Cult of the Amateur' warned of this: a world where opinions and unverified info get equal status with expert analysis.

We have seen this in multiple forms. Early-2000s bloggers gave you "the inside scoop"; the 2010s influencers manufactured authenticity (think 'caught me in fitspo gear totally by accident') to build parasocial trust. Grifters who make you part of their synthetic, performative 'inner circle' so you’re more likely to believe them when they say you can cure death by shoving chia seeds up your bum.

These hucksters capitalised on our craving for self-discovery and agency: key psychological motivators. As experts and governments kept telling us to stay apart so as not to wipe out every granny, social media handed us answers and the illusion of control. Repeatedly, those answers appeared in podcasts and their orbiting pundits. "Rogan et al., 2025" became a citation.

The trouble is, when experts, governments, and the media demand we follow the rules, psychological reactance means we seek those who defy the current narrative, fuelling the popularity of Temu Jack Sparrow Russell Brand, and with him, a digitally-reassuring torrent of microphone-in-front-of-brick-wall people sloppily recommending supplements and life hacks. Climate change? Don’t worry, it’s not real. It’s actually a manifestation of 'Jesus riding your dragon self' or some such tearily-delivered reassurance.

Slowly, the visual aesthetic of a podcast snippet came to be an alternative to expertise, but the reimagining of it. "Nine out of ten dentists" became "someone said it on a podcast somewhere", ideally in front of a red curtain or exposed brick.

The ethical question: Just because marketers can hijack trust, should they? Falsely invoking a High Council of Dentists was already dodgy, but at least it didn’t contribute to the End of Science. By embracing the “somebody on a podcast knows more than the entire scientific community” aesthetic, advertising legitimises the tropes and substance of this pseudo-academic, quackish frontier. And it’ll be even more tempting to do so now that AI video generation lets us conjure fake people having an informative chat without hiring desperate, out of work actors (who’ll now be out of even more work).

So if you are a brand tempted by this UGC podcast-style shortcut, maybe think again.

Consider the cultural currents you are propping up. Those choices validate a digitally illiterate, self-directed relationship with truth. When you draw on the same template as the Gibsons, Brands, and the “just-asking-questions” crowd, it props them up along with the framework and style that imbues their messages with psychological appeal.

Purpose-led brands and organisations can reimagine this space to give something back: affect, rather than be affected by. If you want a UGC or podcast aesthetic, find an actual expert and inject some real knowledge into the medium that displaced it. We can borrow influencer learnings: maybe what audiences need is not another boring explainer or a montage of sad polar bears. Maybe what audiences need is not an earnest explainer of a dire issue, or a stock-video montage with sombre music about sad polar bears, but rather a lively, authentic conversation between real experts speaking to the audience on their level.

As we face another term of the childish flesh Wotsit in the States, what we need less of is people with zero qualifications appearing to know what they are talking about. Even less, people acting like those people. And worst of all, AI people seeming like those people acting like people.