How FCB and Hyundai’s Talking Trees Get to the Roots of Climate Impact

“Hyundai’s purpose, ‘Progress for Humanity’, isn’t a slogan. It’s a belief that innovation must serve something greater: the planet, its people, and the shared future we create together,” says Daniel Roversi, VP, executive producer at FCB New York.

Hyundai’s ‘IONIQ Forest’ programme has embodied this philosophy for a decade, and this summer saw the milestone reached of a million trees planted, across 13 global regions.

Despite these ecological efforts, and that of other organisations, Hyundai’s creative agency partner FCB New York says that only 5% of climate coverage mentions deforestation. Thus, an idea began to sprout: How can Hyundai and FCB increase the reporting of this key driver of global warming?

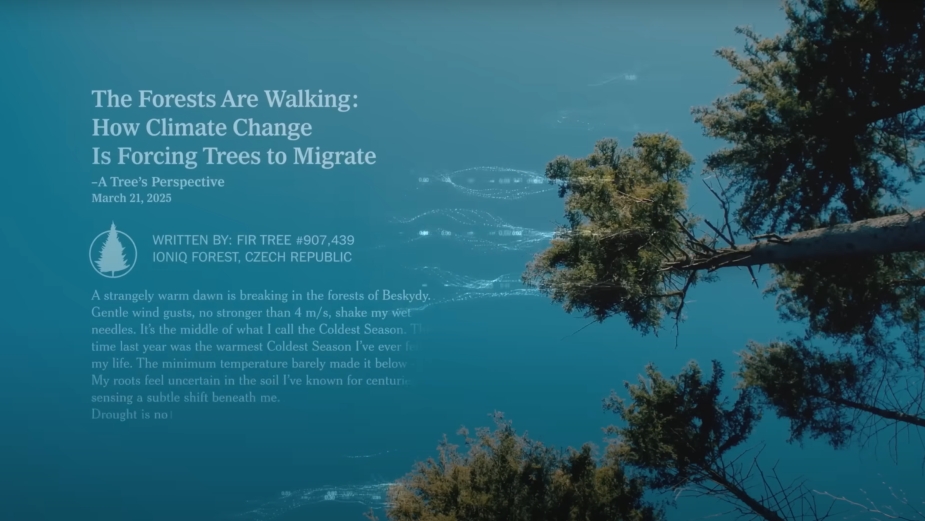

Enter Tree Correspondents: an AI tool that turns trees into data-enhanced storytellers. Powered by environmental sensors, weather APIs, and a proprietary chain of Large Language Models, the system turns soil moisture, sun exposure, and temperature fluctuation readings into reporting sources straight from the forest floor. The insights are then shaped by human writers into first-person narratives, giving each tree a distinct voice rooted in real-time data.

The campaign won two Gold Lions and one Silver Lion in the Digital Craft category at Cannes Lions 2025, and a new round of tree dispatches was released in July — from a Silver Fir in Czechia, a Juçara Palm in Brazil, and a Tulip Tree in South Korea.

Following this latest round, FCB New York’s Daniel Roversi told LBB all about the process behind creating the ‘Tree Correspondents’, as part of the ‘Problem Solved’ series.

The Problem

The Hyundai Motor Company wanted to mark two milestones for its IONIQ Forest initiative: the 10th anniversary of the programme and the planting of its one-millionth tree. The challenge was to recognise these moments in a meaningful way, shifting the focus toward the broader story of the trees themselves and the ecosystems they support.

We wanted to create a meaningful brand act that truly added to the cause… Planting trees was great, but to create real global impact, we needed to bring deforestation into focus so it couldn’t be overlooked. So, we asked ourselves: what if the trees could speak for themselves? If we can get more reporting on deforestation, we can shift the public agenda and create real change.

Ideation

In journalism, when there’s a crisis, newspapers send correspondents. But forest crises often happen in remote places, far from human eyes. Journalism is built on credibility. Reporters don’t speculate, they cite trusted sources. That’s why in moments of crisis, correspondents report from the front lines.

But deforestation has no such witnesses. No embedded reporters. No credible voices from nature’s side of the story. So we turned the trees themselves into correspondents, the natural spokespeople for the forest. Because when a tree thrives, the forest thrives. And when a tree suffers, the forest suffers.

Since people don’t connect with dry data but with stories, we avoided charts and cold facts. Instead, we let the trees tell their own story, one a person could relate to. The project was about one thing: creating empathy for the natural world.

We knew we wanted to turn trees into storytellers, so our first step was research. Trees are more than plants –they’re living archives, carrying data, memory, and wisdom. In literature and popular science, they’re often portrayed as intelligent, social beings. Peter Wohlleben’s ‘The Hidden Life of Trees’ even reimagines them as alert, networked organisms, capable of communicating, caring, and remembering. So, our goal was to unlock that intelligence and let the trees speak for themselves.

To unlock tree intelligence, we first had to define what ‘a tree’s voice’ could realistically mean. This required building a correlation framework between measurable tree data and human-like expressions of emotion. For example, soil moisture, precipitation, and air temperature were mapped to states such as scarcity, abundance, stress, or comfort. These correlations provided the tonal foundation for how a tree might ‘feel’ in a given moment.

At the same time, we introduced journalistic, scientific, and philosophical knowledge bases so that the LLMs had a clear frame of reasoning ensuring the outputs were structured as articles rather than raw, unshaped narratives.

Lastly, we introduced a human-in-the-loop tuning process. While the AI generated first drafts, our editorial team refined them, adjusting tone, validating factual integrity, and ensuring the narratives struck the right balance between scientific precision and emotional resonance. Each round of feedback informed further prompt engineering and data-to-emotion mappings, effectively training the system to improve over time.

Together, this approach allowed us to translate hard data into human-readable stories, creating distinct personas for each tree that could report on its environment with both credibility and emotional impact.

At one point, we explored giving the trees very distinct, almost poetic personalities, but quickly discarded this, as it risked undermining credibility. We also considered producing fully automated articles without human intervention, but those outputs lacked the nuance required.

One of the biggest challenges was striking the right balance between scientific accuracy and emotional resonance. Too technical, and the articles read like climate reports. Too emotional, and they felt like fantasy. We cracked this by iterating: running outputs, editing them, refining prompts, and feeding the learnings back into the system.

Also important is the speed at which AI is moving. That was inspiring in itself. Every week a new development would drop, and the project would take a turn. At the end, the full process showed us how humans and AI can collaborate in shaping narratives.

Ultimately, the inspiration was the trees themselves. Silent witnesses whose stories, if told, could make climate change feel human and urgent.

Prototype and Design

One of the most interesting aspects of the design and prototyping process was figuring out how to give voice to an entity that collects vast amounts of intelligence but has no language. This required going beyond data collection into persona creation.

Another fascinating stage was embedding domain-specific knowledge bases into the system. These resources, ranging from journalistic style guides to climate research and philosophical texts, provided the LLM with a frame of reasoning that shaped outputs into structured dispatches with clarity, context, and narrative flow.

Conversations with [creative coding and visual art studio] Uncharted Limbo and our partners, drawing on references from nature writers, philosophers, articles, and ecological studies, were critical in determining how much factual grounding and stylistic framing the system required to balance credibility with creativity.

Finally, the human-in-the-loop tuning process proved invaluable. Early outputs were often abstract and unfocused, highlighting both the strengths and limits of generative AI. Through iterative prompt engineering and editorial feedback, we were able to refine the model’s responses demonstrating how human guidance remains essential in augmenting AI, especially in contexts where factual accuracy and narrative integrity must align.

To bring this project to life, we integrated a diverse group across multiple disciplines. We partnered with Uncharted Limbo, a trusted creative tech partner, used The METER Group’s sensor and software tech to capture real-time cloud-connected data for environmental local tree data collection, and consulted with Biomimicry 3.8 for ecological insights and article validation, and Dan Richards as journalist editor.

One of the most interesting challenges was aligning our collective intelligence… And equally complex were our conversations with local ecological NGOs. Convincing them of the project’s integrity required transparency about how the system worked, how sensor data would be captured, how it would be transformed into narratives, and how we would ensure factual grounding.

Finally, the most fascinating internal discussions came from shaping the AI itself. Early outputs leaned heavily into poetic abstraction, which sparked debates about whether we were drifting too far from journalism into metaphor. Our editorial process became a proving ground for how humans and AI could collaborate: AI to process and draft, humans to tune and refine. Those conversations ultimately defined the middle ground we landed on; journal entries rooted in data but shaped by emotion.

Developing an agentic pipeline to craft ecological articles ‘in the voice of trees’ entails a complex array of risks across multiple phases. On the technology side, challenges include ensuring accurate interpretation of environmental sensor data, building models that can convincingly simulate non-human perspectives, and maintaining reliability and transparency in AI-generated content. From a logistical perspective, deploying sensors across diverse and often remote ecosystems in partnership with NGOs introduces risks related to hardware, data integrity, and consistent global coverage.

Beyond these, there are also societal risks. We introduced this project at a time when the press is undergoing a trust crisis and AI is reshaping how humans interpret truth and narrative. Some might view the idea of trees speaking through AI as poetic and powerful; others could see it as manipulative or a further blurring of the line between fact and fiction. The risk lies in whether audiences interpret these dispatches as credible journalism, speculative storytelling, or something in between.

To address this, we emphasised transparency in how the narratives were created, making clear the role of sensors, data, AI, and human editors, and opening our process to readers in TreeCorrespondents.com where they can learn about the process of making of the project, read articles, and find the sources from which each article’s claims were built – all this to avoid misleading audiences.

The challenge, and the opportunity, was to use AI not to replace journalism, but to extend it into underreported ecological contexts. Still, the societal reception underscored the responsibility of deploying such work carefully, ensuring it contributes to trust-building rather than eroding it further.

Live

The process of prompt engineering in this project is inherently fluid and iterative, leveraging frameworks like LangChain, embedding models, RAG, and agentic architectures, while keeping humans in the loop for continuous tuning. Prompts are not static instructions – they evolve as we test, evaluate, and refine outputs, using embeddings (which turn the words in a prompt into a numerical code that the AI model uses to understand the context and relationships of a request) to align semantic meaning and context across data sources.

Agentic pipelines enable the AI to take structured actions, but human oversight is critical to guide reasoning, correct errors, and inject domain expertise. This combination creates a feedback-driven loop, where prompts, embeddings, and agent behaviours are constantly adjusted based on results, ensuring outputs remain accurate and contextually rich.

The system is continuously ingesting real-time sensors and external environmental data. As the system is run, their inputs provide additional contextual feedback that can inform future outputs. That said, refining the AI’s reasoning and improving the fidelity of ‘tree-perspective’ would require engineering-level interventions beyond what user interactions alone can achieve.

The most personally fascinating aspect has been exploring forms of intelligence beyond the human, particularly tree intelligence, artificial intelligence, and how they can intersect. Drawing on Pierre Lévy’s concept of collective intelligence, which emphasises a shared, emergent intelligence arising from the interaction of multiple actors and knowledge systems, this project experiments with a non-linear, non-aggregative form of intelligence. It is not simply the sum of human insight, sensor data, or AI reasoning; rather, it is a generative space where these distinct intelligences collide and come together into entirely new forms of understanding.

In this sense, the project treats the tree and the algorithm as interconnected nodes in a network. The narratives that emerge (written in the voice of trees) represent a collective intelligence that neither could produce alone. This fusion challenges traditional notions of authorship, cognition, and knowledge creation, opening a space to explore how hybrid intelligences might inform understanding and storytelling in ways uniquely attuned to both human and non-human systems.