How Viral Horror Director Dylan Clark Tortures His Audience

Dylan Clark has a penchant for making audiences uncomfortable. The writer and director of horror shorts has been tormenting and entertaining a growing online fanbase with his inventively disturbing worlds.

At 23, he seeks to finally answer horror buffs’ calls for intelligent characters and thrills that go beyond jump scares. Most recently, he’s treated them to ‘Storytime’, in which the line between fiction and reality is alarmingly blurred for a crime podcast listener; ‘Remains’, which sees a grieving mother suspect something lives inside her infant son’s urn; and ‘Portrait of God’ – currently sitting at over 5.4 million views – where a religious girl is forced to come to terms with her faith when she analyses a provocative painting of God.

To find out exactly how he toys with his audience – or as he puts it, wages “psychological warfare” on them – LBB’s Zara Naseer speaks to Dylan about making the most of the resources you have, the role of music and sound, and why suspense is often the best form of torture.

Above: Director of horror short films, Dylan Clark

Above: Director of horror short films, Dylan Clark

LBB> To start from the beginning – what was the first horror you made? How has your process changed since?

Dylan> The first was this found footage, ‘The Blair Witch Project’-style film that my friends and I made in the woods by my house at around 11 years old. Super scrappy, terrible, but a huge passion project. Everything about the way that was made was unique, because we learned so much after.

It was around that time that short horror content became really popular on YouTube. ‘Lights Out’ went hugely viral and showed that you could do more with a lot less, even keeping it contained to one actor; our first short had several kid actors pretending to be teenagers in the woods, lots of kills, and it didn't work at all. So future projects dramatically changed: they became smaller and more precise, determined and locked in, versus sporadic.

Above: Dylan Clark's viral horror short, 'Portrait of God'

LBB> The horror in your films comes from the lofty (religion and grief) to the mundane (a podcast or grocery shop). Where does your inspiration come from?

Dylan> It comes from the resources we have, because if we're going to go out and make a short, we have to first know we can do it. For ‘Hatched’ with the groceries, for example, I was stuck in my apartment with my roommate, and I knew that we had access to a kitchenette and these very specific items in our apartment, because we literally couldn't leave it during lockdown. So our apartment became our sandbox, and we thought, what if someone unknowingly brought something sinister from the grocery store into their mundane apartment?

That's how I’ve operated for so long on a really scrappy indie level; now that I have a little bit of access to more resources and people, I am thinking more broadly about what could come next!

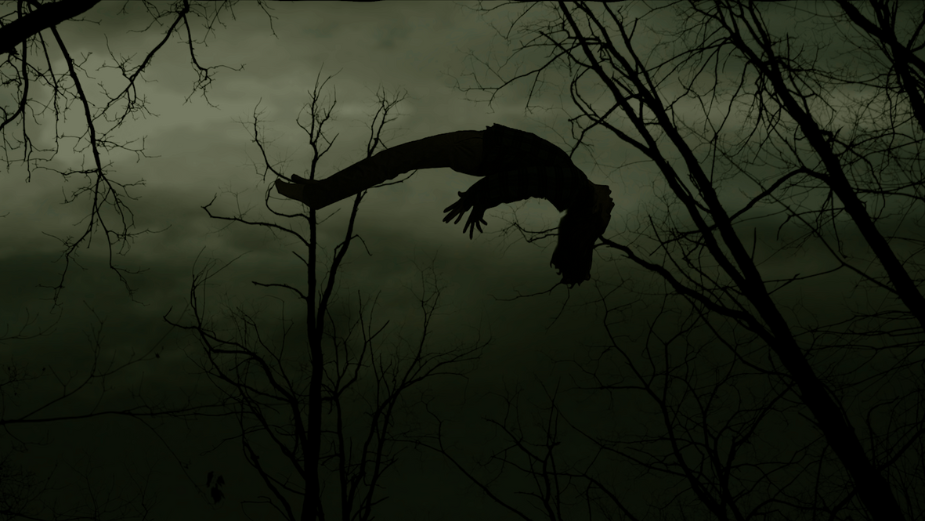

Above: Still from 'Rest'

LBB> Intelligent characters, a lack of reliance on jump scares, and attention to detail are what really makes your films stand out. Is this part of some guiding ethos?

Dylan> I watch a lot of horror, and you quickly notice the typical tropes and structures. Some really work, and others really don't. For me, there’s a checklist of things that I really want to see – or not see – in a short horror film, which guides my craft.

Especially with intelligent characters, I always think that if your character can run away, they should try to. And usually they can. So in most of my recent shorts, there's at least one moment where someone does try to escape or grab a weapon, and having a moment like that can go a long way in making a film feel a little bit more believable, and a little bit more refreshing.

Above: Still from 'Remains'

LBB> You’ve previously said that you can “really torture the audience in horror by simply doing nothing at the optimal moment” – tell us more.

Dylan> For getting into your audience's head, you need to know when lingering on nothing and leaving them in suspense is the most torturous thing to do.

There’s a key moment in ‘Storytime’ when the door swings open and everyone can sense something really dramatic is about to happen; but if we did it right away, we’d have lost this 10 second window of total torture. We’d thought of some narration there but it became very obvious that it should just be him, stood staring at the camera for however long it goes.

It's the same in ‘Jaws’ – showing an open body of water, knowing that there is a shark out there somewhere, is so much scarier than a shot of a shark swimming by. It's something I think about with each project, and we find the moments to really lean into it. It becomes obvious in the edit where that wants to be played out.

The same goes for music and sound, which I think are probably more important in horror than any other genre (except musicals). It’s about knowing when to lean into it and when to lean off it, because there are certain moments where being aggressive with sound is what's going to bring the scare, and others where too much is actually subtractive of the tension. Total silence leaves the audience to expect a sudden spike – it’s total psychological warfare.

Above: Still from 'Storytime'

LBB> Your films feature some very compelling acting – do you have any methods for eliciting the best performance?

Dylan> In ‘Storytime’ and ‘Portrait of God’, the lead was played by Sydney Brumfield. She's a good friend of mine who’s also a writer and super multifaceted, so our shared understanding is really beneficial.

What I’ve found most helpful is to have those conversations ahead of time, especially when it comes to dialogue or blocking. The location for ‘Storytime’ was Sydney's actual apartment, so we were able to come in ahead of time and run through the whole film as much as we could with our cinematographer. We went through the script, the key beats, and the emotional arc of the film, where she’d be absolutely terrified versus intrigued.

So just having conversations ahead of time is the most helpful in the short term, and building a continued working relationship is great for the long term.

Above: Sydney Brumfield in 'Portrait of God'

LBB> You mention in your ‘Hatched’ making of video that messing up can often make you stumble upon a better idea - what’s your favourite example of this?

Dylan> The scare near the end of ‘Storytime’ was written and shot completely differently. Now, it comes from something which was there all along, which you’d have thought we’d planned from the beginning; but for some reason, when we wrote it, the scare was that the rules had changed and the podcast could contort her on its own. It was a happy accident where the set up was always there, and we realised we could stick to this iconography throughout that feels so much tighter and more considered from start to finish.

Above: Still from 'Hatched'

LBB> What keeps you in love with horror as a genre? And which filmmakers?

Dylan> Horror is so flexible as a genre – it can cross pollinate with other genres quite nicely – which keeps it refreshing year after year. The majority of the filmmakers I admire most in this space take advantage of that. I'm a huge fan of Mike Flanagan, whose work is quite varied: it's driven by characters who are so different, which allows him to tell very different stories. I also love Guillermo Del Toro and how he blends a fairytale, fantasy, or even Gothic sensibility into the horror genre.

Above: Dylan Clark's horror short, 'Remains'

LBB> What can audiences expect to see next from you?

Dylan> In the short term, I'm finishing up a short which is a little bit longer, and more about a conversation between two people. A lot of my shorts have been very dialogue-free, and this is the first one that really leans on it as the crux of the actual story. We’re in post with it at the moment, and hopefully we'll be sending it out to film festivals in a couple of months.

In the long term, I’d love to make a horror feature. It takes so much aligning, but I have a couple of things that I'm really working on and pushing to hopefully get made.

Above: Still from 'Seagrass'

LBB> Finally, how can the industry better support promising young filmmakers like you?

Dylan> There's almost a veil of uncertainty about what the industry looks like until you're actually immersing yourself in it. Some people are starting to open up and speak more candidly about how they’ve managed to progress in the industry, and that's something that I'm hoping will continue and that I'd like to contribute to. I wish people would be more open in a productive way that's accessible to everyone in places where people are looking every day.

Above: Still from 'Portrait of God'