Changing the Culture of Caregiving in Cancer

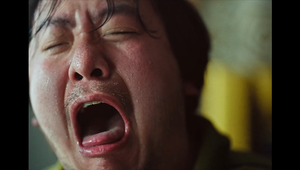

Photo: Sarah Jane and her Mum, Angela

With World Cancer Day just around the corner, it’s struck me that 2024 will be my 10th year working in metastatic breast cancer (MBC). In that time, MBC has transitioned from being a focus for my client work, with no personal meaning, to a disease that changed my life forever. Here’s my reflection on the impact of cancer and caregiving on my career, and the role of self-care and workplace culture.

Eight years ago, I took on a second job. It was a job I never applied for. A job I wasn’t qualified to do. And a job I didn’t want to end.

I became a caregiver to my mother, Angela.

My mum was diagnosed with MBC in 2016, just two months after she had entered remission for early-stage breast cancer. The cancer had metastasized to her brain and liver, a diagnosis we both knew had no happy ending. For the next 18 months – while trying to manage client work that brutally exposed me to the realities of MBC – playing a key role in my mums ‘care unit’ became priority number one. It was the best, worst job.

The role of caregiver is uniquely personal; everyone’s experience is different. We know ‘it’s not about us’, it’s about the person we’re caring for, but that doesn’t make the challenge any less overwhelming. It’s an emotional rollercoaster you experience together. When they are up, you are up; when they are down, you feel helpless.

One of the golden rules of caregiving is ‘self-care’, but when your focus is fixed firmly on the person you love, that’s easier said than done. Staying in control of your own health is an everyday battle, and sometimes one you don’t notice you’re losing. Evidence suggests that, in advanced cancer, informal caregivers typically provide 18-33 hours of care a week to their loved ones, often on top of other jobs. The physical burden of that – as well as the silent toll on your mental health – is significant, yet emotionally we just don’t prioritise it.

The impact of not taking care of yourself hits hardest where it matters most; it can only compromise the quality of your caregiving. As the metaphor goes: if you don’t put your oxygen mask on first, how are you going to help others? My conversations with fellow caregivers – many of whom recalled times when they were sick or felt ‘ready to break’ – revealed that, for all of us, self-care was only an after-thought. We couldn’t, in the moment, see that it was so important.

Self-care has become a familiar topic of discussion among caregivers, but much more is needed to raise awareness and provide effective support to those caregiving for their loved ones. Common advice – listen to relaxing music, take exercise, find time for mental breaks – is sensible and well-intended, but when you’re in the jaws of caring for a loved one, the reality is very different. Self-care in advanced cancer is complex. A deeper conversation is required.

One component of self-care that sometimes flies under the radar is workplace culture. We spend a third of our lives at work – through good times and bad – so when cancer strikes at the heart of our world, whether living with a diagnosis or taking on the role of caregiver, our workplace environment can have a big influence on how you cope. Employers have a big role to play in helping caregivers navigate the challenges by establishing cultures that actively support self-care, making space and adjustment to a new normality.

So what does good look like? As employers, team leads and colleagues we need to develop a deeper understanding of people and their circumstances – allowing space, offering flexibility, and relieving pressure as people grapple life with cancer. There’s also a need to recognize that life after cancer (whether that’s cure or loss) is different. An empathetic environment enables integration back into the workplace and recognises new/different motivations and needs. Workplace attributes and culture can have a big influence on caregivers’ ability to look after their own health whilst, at the same time, manage two jobs – their professional role, and the most important role they’ll ever have: caregiving for a loved one.

Personally, I have been supported to use my caregiving experience and loss from cancer as a platform to find renewed purpose at work, and most importantly take small steps to advocate for and improve the experience of those living with metastatic breast cancer. Our connection to the advocacy community has never been stronger, inspiring better work, driven by an ability to understand and empathise with those affected. Having the opportunity to focus on an area of personal meaning, makes my life at work sometimes emotionally harder but often much more rewarding.

Eight years ago, I landed a job I never wanted to begin or end. Sadly it ended in September 2017 when mum passed away. It’s not really until you’ve been through a caregiving experience that you have the mental space to think about the impact it’s had on you and the learnings you can take from it. My overriding reflection is a simple one: it takes a village to provide the best care possible to those we love. More can and should be done to help ease the challenges that caregivers face. At its simplest level caregivers need to be recognised, more support is needed across the board, and some of those solutions can be found in the culture we build at work.

So, if you’ve experienced something similar and can recommend anything else that might promote self-care and improve workplace culture around cancer, don’t be afraid to share it. Let’s get the conversation started to give caregivers a voice and take steps to change the culture of cancer for good.