Turning a Rube Goldberg Machine into a Metaphor for Weight Management

There’s a reason eye-catching visuals remain a go-to in advertising: they grab attention fast, no matter the product. So, the decision to construct a Rube Golderberg machine from scratch and centre a spot around it is an inherently clever idea, but if it also proves to be thematically appropriate? You end up with something special on your hands.

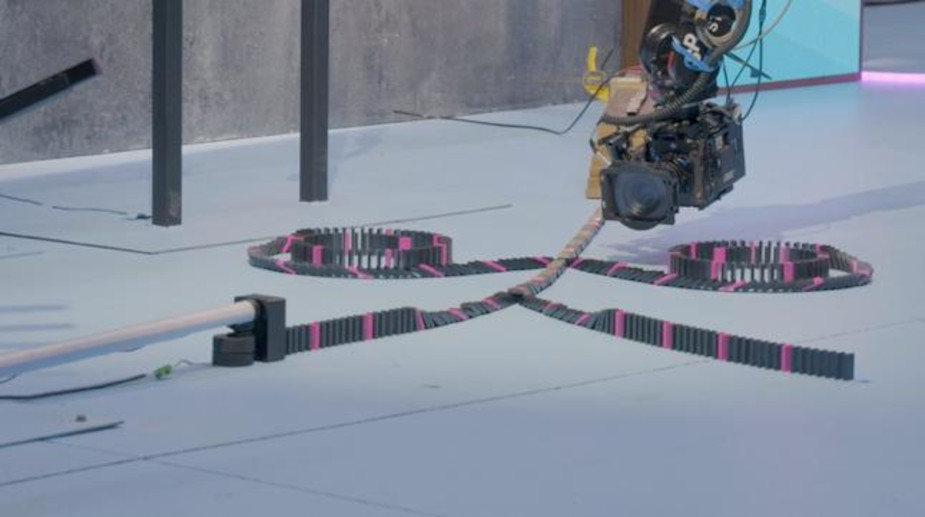

Such is the case with a recent campaign for Wegovy – a weight loss medication – created by No Fixed Address and brought to life by Partners Film director Arno Salters. Designed as a visual metaphor depicting the ups, downs and momentum that comes with finding a solution for weight management, it’s an intricate, visually-striking and, crucially, memorable way to get this message across. After all, it’s not every day you spend 30 seconds of your life watching a marble set up a chain reaction which leads to a sign being activated. But, when it happens, you can’t help but wonder exactly how it was brought to life, especially when the entire thing was clearly done practically.

For that reason, LBB’s Jordan Won Neufeldt sat down with Arno for a chat, going over how the machine was built, what it took to shoot around such a unique creation, and why it was so important to put in this effort in an era when AI creations are growing more and more common.

LBB> From the top, what was the brief for this project, and why was this something you were keen to be involved in?

Arno> The brief was to create a Rube Goldberg machine that would act as a visual metaphor for the ups and downs of one’s journey towards a goal – in this case, weight management. (The creative concept being to represent that journey as momentum towards a solution: Wegovy).

The team at No Fixed Address had some ideas for the machine, but they were also very open, collaborative and trusting on execution, which was exciting and incredibly freeing. In truth though… they had me at ‘Rube’.

LBB> What was the actual planning and executive process like for designing a Rube Goldberg machine? Tell us about how it came together!

Arno> It was really important to me that we actually build this machine and film it practically, rather than relying on CG. There’s a textural and visceral authenticity that comes with crafting this kind of visual magic trick for real. Ultimately, the result is so much more satisfying and visually exciting than if you rely heavily on post.

Building the machine and shooting it practically made the pre-production process pretty involved, because whatever we designed had to actually work within the 30-second run time of the film.

Step one was to take the ideas in my treatment and draw a concept sketch – or two – with production designer Jesson Moen, and his render artist, Sebastian Harder. Not so much storyboards, but rather wide shots of the machine, imagining the path from start to finish. You can see one of our later sketches below.

Once this sketch had been turned into design renders, step two was to build a 3D-previs with Artjail, trying out different camera moves and adjusting the design as we found things were too fast, too slow, etc. Our DOP, Chris Mably, was also involved at this stage.

Step three – which was happening parallel to the previs – was for Jesson and his team at Crux Design+Build to actually engineer and test out each part of the machine practically. Not only was this important for making sure all our theoretical sketch ideas would work, but also, to test the timing of things (how long does it take for a marble or the dominoes to get from point A to point B? Do we need to shorten the distance? Should we add a loop?, etc.). We then took our findings back to the previs and adjusted accordingly.

The final step was to get our motion control operator, Nigel Rowe, involved, so he could confirm the moves we had imagined would work, and if not, then adjust accordingly. This back and forth dance (AKA daily Zoom calls) went on for a while, until we got to a previs we were all excited about, and that felt as true as possible to what we could achieve come shoot day.

LBB> At the same time, how did you prepare to actually film the machine in real time? What sort of rigs did you have to set up in order to make it possible?

Arno> The machine was engineered and built at Crux. The team was brilliant at figuring out engineering solves for whatever ideas I’d had, but the tricky part for them was, firstly, having to adjust things constantly based on previs findings – for instance, we realised we needed to lower the marble/cog wall by 2 feet just before the shoot, because it was going to be too high for the motion control – and secondly, ensuring we had a certain amount of timing flexibility built into the machine. After all, it doesn’t matter how well you prepare for a shoot, surprises always pop up on the day.

To address the latter issue, wherever possible, the team made it so we could extend or shorten certain portions slightly. For instance the start of the marble ramp had an adjustable incline to slow down or speed up the ball, as did the zipline, and the counterweight system on the rising hand after the dominoes.

One concern we had up front was the amount of time it would take to reset the dominoes between takes. We only had two shoot days, and that alone felt like it had the potential to take half the time. So, Crux developed these clever guides that allowed the team to install the dominoes in the right formation on the side, and then fly them in, already in position, once a take was done.

LBB> What sort of equipment did you use for the shoot?

Arno> I find that with Rube Goldberg machines, most of the time, people will put a tonne of energy into designing something amazing, but then shoot it in quite a bland way – like a slow-moving wide shot.

I really wanted to approach this one like the action movie version of a Rube Golderberg machine – an uninterrupted, fast-paced shot where the camera travels precisely within the machine, shifting with sharp dynamic moves from first-person type angles to wider perspectives (whenever that was required for legibility).

The only way to shoot this kind of fast, intricate move practically was on a Bolt X motion control rig (shot with an Alexa 35). It’s an incredible tool, but also has a bit of a mind of its own, so doing something this complex with it really required tapping into meditative zen vibes when programming.

LBB> From here, what was the filming process like?

Arno> On set, I would say the hardest part was programming the Bolt X to recreate what we had envisioned in the previs. You can, in theory, export the move from a previs directly into a motion control rig, but it never quite translates in my experience. So, once the programming was done, the rest was mostly smooth sailing.

LBB> Was it the type of project where you had to capture the entire sequence in one go, or were there multiple takes focused on each section? And, as a whole, how did you get the best perspectives for each?

Arno> We did break it up into sections, mostly because we had to move the base of the Bolt X a couple times. So, there are a couple hidden cuts as a result – one of which actually involved a lens change. Specifically, we shot the first portion of the film on a 45-degree probe lens so we could get that awesome moment with the camera chasing the marble through the light tunnel (with the probe lens fitting through a tight trench at the top of the tunnel, which was later filled in in post), and then the rest on a prime lens, with matching focal length. Artjail made that stitch totally seamless.

LBB> Of course, the final spot had to be visually appealing as well. How did you go about this?

Arno> One of the key aesthetic elements that works so well here is the integration of practical lighting within the machine. This required close collaboration between Chris and Jesson to ensure the machine would be built with the integration of those lights in mind.

Equally important, however, was Clint Homuth at Artjail, who did an amazing job colouring the film, giving it a filmic look with vibrant colors.

Finally, on the soundscape side, BoomBox did an amazing job with machine foley and live jazz drumming, captured to match the narrative journey of the machine.

LBB> Through all of this, were there lessons learned along the way? Tell us about them!

Arno> I discovered that two same-shaped objects will drop at the same speed, no matter how light or heavy. Basic physics… which I wasn’t aware of until picking a ball for the opening shot.

LBB> Finally, are there any elements of the project you’re particularly proud of? And why?

Arno> I’m proud of the fact that we captured this in camera. As more and more AI footage floods our feeds, I think practical craftsmanship in filmmaking will become exponentially more special and exciting for the viewer.