Ad Astra: Andy Bird on Freedom, Fear and Creativity

2024 kicked off for Andy Bird with the launch of an ambitious bit of pioneering AI creativity – Publicis Groupe’s ‘Wishes’ project, which this year used generative AI to make 100,000 unique, personalised videos. It’s a campaign that saw him wrangling cutting edge technology as it convulsed and changed in his hands, evolving, more or less, in real time. But, he reflects, in a sense, it really wasn’t all that different from the work he was doing right at the beginning of his advertising career.

“Going back to when I was cutting up bits of Letraset 40 years ago to cutting together other people’s voices to be replicated by a machine 40 years on – it’s the same thing,” he says. “I just think it’s a tool.”

He says he was “petrified, not knowing what I was doing” – but as we’ll see, feeling that fear and feeling singularly clueless, but having a go regardless, is a pattern that we’ll see repeated throughout Andy’s career. It’s there whether he’s taking his first steps as a creative, becoming a chief creative officer for the first time or, indeed, relearning what it means to be a creative director in the AI age with a high-visibility, live project.

“I’ve never lost the fear of a first brief,” he says. Andy has been in the advertising world for over 40 years. In that time, he’s been involved in countless iconic campaigns, honed his craft under the scrutiny of Sir John Hegarty, and has led multiple agencies to success. And yet, he says he still can’t shake the feeling that somebody is going to tap him on the shoulder and say “‘Enough of this now, go and get a proper job!”

“I think that’s a good thing because if you get complacent and think you know it all, maybe you won’t come up with the best ideas. I always have that nervousness. And then – and I think any creative person will say this, not just me – I love it when you feel you’ve got something … and you can’t wait to show someone.That’s a great feeling.”

In 2021, Andy became a founding partner at Publicis Groupe’s elite creative collective, Le Truc – the perfect home for someone who’s pathologically incapable of complacency. It’s a crack team of about 60 that works across the Groupe, occasionally fronting creative work but often parasailing in to help agencies that need some extra oomph, or adding fresh perspective to big pitches. Andy’s one for four chief creative officers in the team – he’s joined by Julia Neumann, Bastien Baumann and Marcos Kotlhar – and the CCOs are much closer to the work and the team than they would be in a more hierarchical set up. Every job is different (Andy describes Le Truc as a ‘shapeshifting thing’) and they’re encouraged – no, expected – to be unconventional in their approach.

Given Andy’s own less than conventional journey into the advertising industry, it’s perhaps unsurprising that he’s found a home somewhere as idiosyncratic as Le Truc. As we’ll see, Andy’s someone who’s learned everything about advertising on the job, often facing up to, accepting and even, eventually, enjoying those scary challenges that lie several steps beyond his comfort zone.

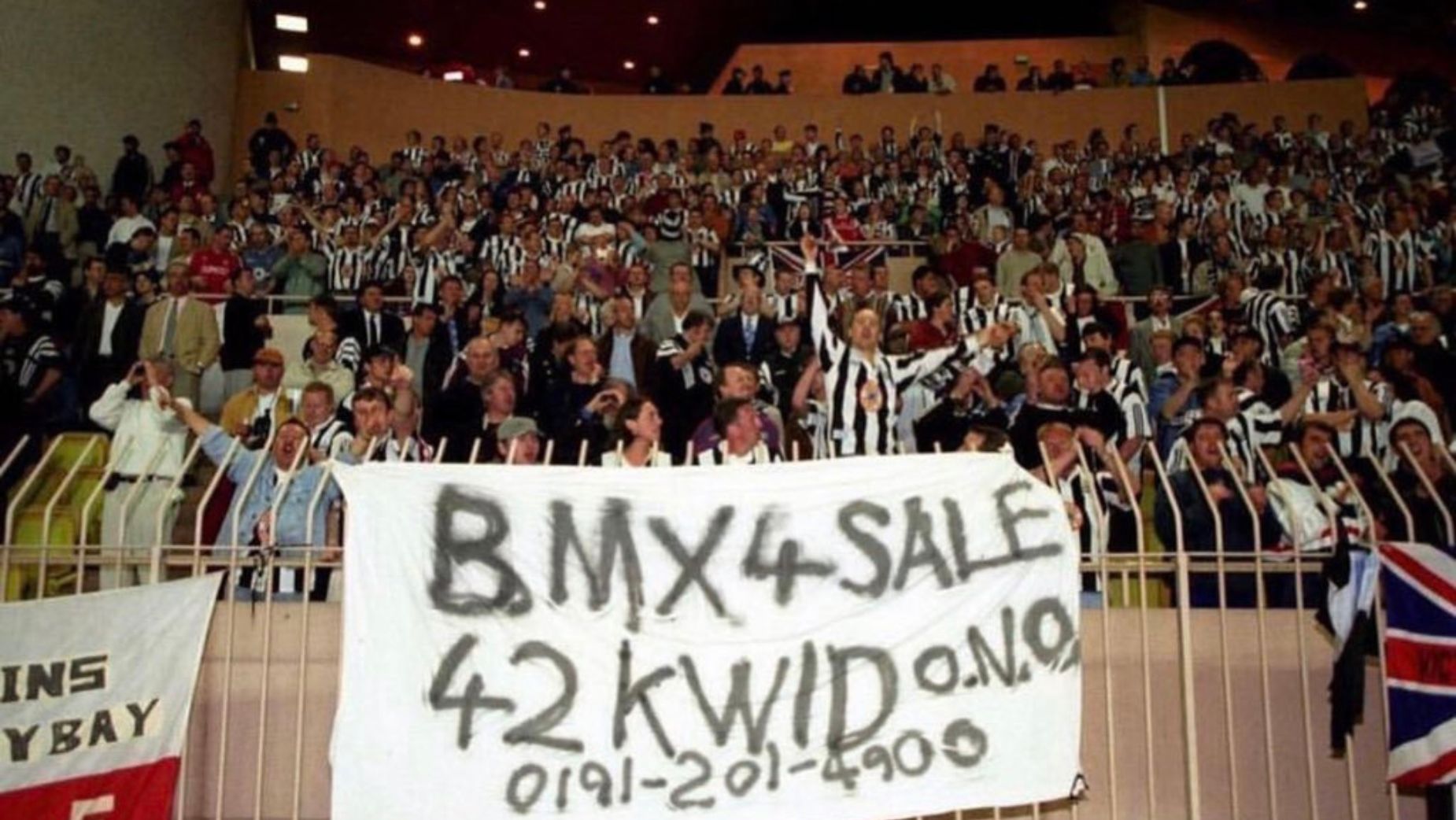

Andy was taught to draw by his grandfather, who was a time commissioner in the shipyards in Newcastle, in the North of England, who kept his own art a secret from others. His other creative education came courtesy of his cousins, who’d been punks in the ‘70s, who got him on a musical diet of new wave, art and watching Newcastle United home and away from the late 70s onwards (see Andy’s famous BMX 4 Sale banner below at FA Cup game against Monaco in 1997, his favourite piece of “work.” At 15, he was heading out to watch bands, getting into soul and funk music too.

Andy’s infamous 'BMX 4 Sale' banner at the European cup game against Monaco vs Newcastle in 1996. Now on permanent show at Newcastle United 28 years later, his ‘proudest’ achievement.

Despite now being able to recall hundreds of ads from his childhood, at the time Andy had no idea that advertising as a job or an industry was a thing. When he left school at 16, with little or no qualifications, he got a part time job as a cleaner in a bakery. The ‘80s were a time of high youth unemployment in the UK and Andy soon found himself on the YTS (Youth Training Scheme). Having told the careers officer that he could ‘draw a bit’, he was placed in a B2B agency.

“I was the art studio dogsbody. I didn’t know what advertising was. I didn’t know how things got made,” he says. It was the first of many times that Andy would find himself feeling out of place and out of his depth. “During that time I applied for a few other jobs – I applied to be a postman three times. To get a real job, because what I was doing wasn’t getting paid like a real working job.”

But then, he ended up staying in that ‘not real job’ for two years, soaking up everything he could in the studio, where the type was designed and the posters laid out. By that point he’d moved down to London and he got wind that McCann Erickson was looking for a junior. “I spent a couple of years there and that’s where I first realised how an agency was built and how things got made, and I was exposed to a creative department – and I was paid. I think by the time I was 20 I decided that I was going to do this. I was petrified because I didn’t know what I was doing, and they didn’t expect too much of me to be honest. I was just this kid,” remembers Andy.

He was learning the craft of typography in the production studio, carefully tracing letters out by hand and developing what he describes as an ‘anal’ attention to detail that means even to this day, poorly laid-out punctuation makes him twitchy. McCann’s head of design Rob Wallace ‘humoured’ him, he says, as he used the agency’s new Apple Macs to make art on the weekends.

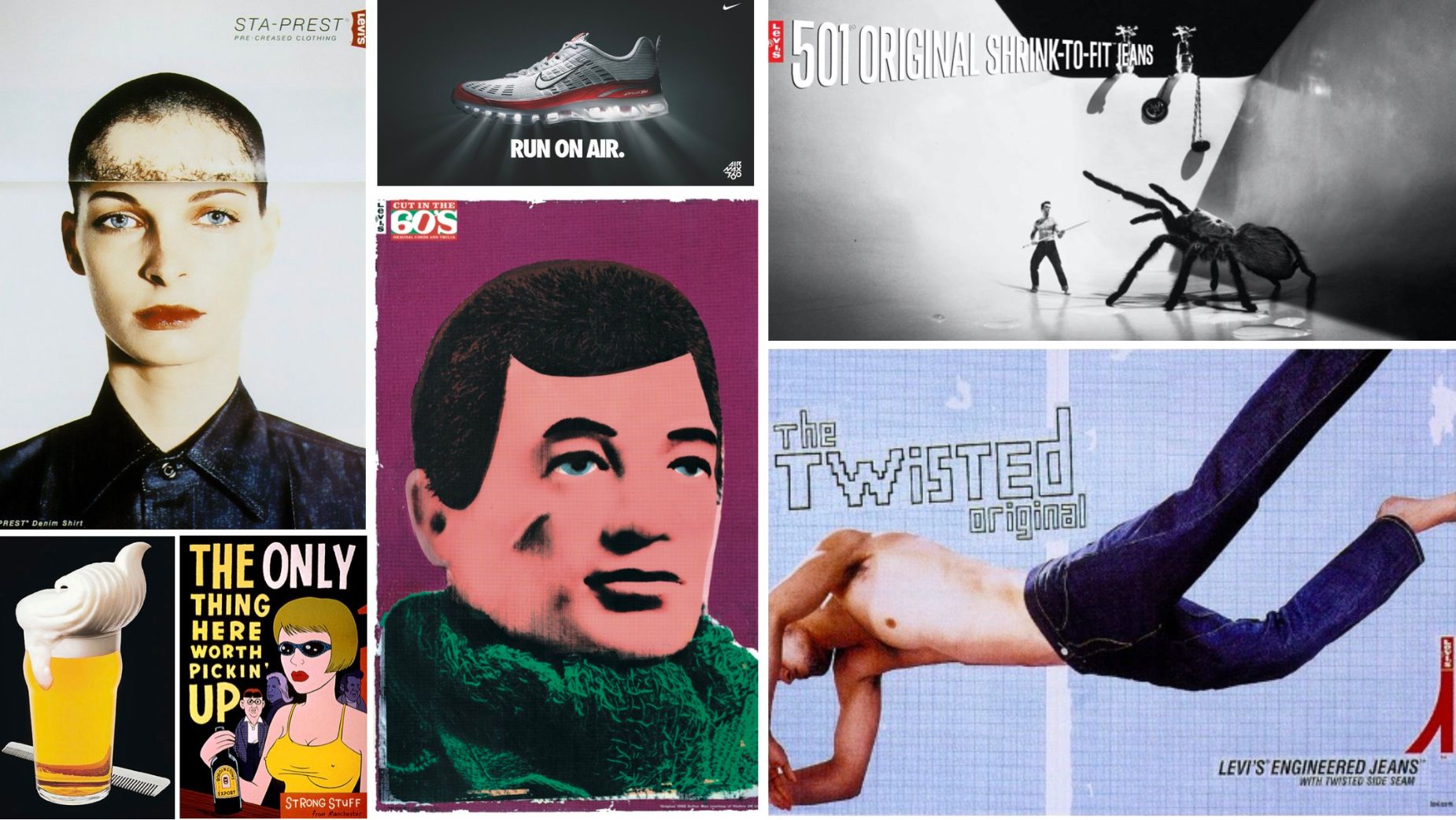

Andy's design and art direction work from the 1990s and 2000s.

(Throughout his career, Andy’s always liked to have creative side projects on the go – for years he ran a fashion magazine on the side called The Rig Out, which is now a creative production studio in London. These days he ‘plays the guitar badly’. “I think it’s great to have an interest that keeps you creative outside of the advertising world,” he says.”)

It was, he reflects, a different world. “That job is long gone. There are designers who are far more expansive in what they do. But back in the day, what I did was put words on ads. That’s simply what I did. I had no influence on what the ad was. It was just designing beautiful typography – if anyone could be bothered to look back, in the ‘70s and ‘80s there were legendary typographers in advertising in the UK, who made art, really. But they didn’t influence the concepts as much as designers do now.”

Now, creatives have every possible media to play with but when Andy was coming up, there was radio, TV, press and poster – and Andy very definitely didn’t touch radio or TV. Starting at the bottom with such a narrow focus has, though, shaped his appreciation for the talent and teams within agencies and the fact that behind the creative work there’s so many skilled craftspeople and specialists that help bring it to life.

Next came an opportunity that would prove to be a crucible for young Andy –the chance to work at BBH. It was a pay cut but he didn’t think twice. There he was immersed in a deeply visual culture under the leadership of John Hegarty. Andy found himself not in a typography department, but a design department. Within eight months he was head of said department. Not bad going for your early 20s, but unlike the graduates just entering the industry at that age, Andy had been working and honing his craft for a good four or five years by that point.

It was a time of great success for the agency. Andy describes the creativity as ‘entrepreneurial’, ‘expansive’ and ‘adventurous’, though it was underpinned by an intense rigour. Andy reels off the creatives who surrounded him and it sounds like a who’s who of London advertising with people like Rosie Arnold, Tiger Savage, Ed Morris, Tony Davidson, Bruce Crouch, Graham Watson and Nick Gill.

“We’re in an era now of multi-layered departments – lots of titles and you have to share the work up. But then, it was John, a few CDs and us. There was no hierarchy. It was very much you had a direct link to him and he had a strong point of view about work. I got from him: clarity, singularity and a maniacal focus on the detail of the work, which, if you look at that period of time for BBH, was everything about them. It was a craft centre.”

Andy recalls that it was about that time that he had his first experience with modern art. He was about 22 or 23 and wandered into an art gallery in Whitechapel, with no clue what he would see. It was an exhibition of Franz Kline, an American abstract expressionist and, he says, the experience left ‘an indelible memory’. “Art has had a major impact on me… I’m passionate about art. I don’t do it enough. I used to do a lot of it,” he says.

That experience coincided with Andy starting to really get his head around the conceptual side of advertising. When he was eventually given that nudge – or shove -–over to creative, that familiar uncertainty kicked in as, once again, Andy found himself facing an unknown challenge. “Back then it was like, you are just making brilliant look even more brilliant. That was my job. But to go in, and now you’ve got to think about the ads… I remember saying, ‘I don’t know how to do TV ads’.”

What didn’t help was that when he did finally land his first TV ad – a Levi’s spot that took six months’ work and a big international shoot – was canned by the client (though it did eventually run in Australia). Speaking candidly, Andy says the experience really dented his confidence. But it also proved to be yet another valuable lesson.

“I learned so much in that place. I didn’t go to college, but that was my university. What a stroke of luck, what a fortunate person I was to be able to learn that.”

From there Andy went to Ogilvy, where he spent five years as an ECD working with Sue Higgs, and then the next big terrifying test came. He was offered the role of CCO of Publicis London. “Again, I’m petrified. Like, what am I doing?” laughs Andy, incredulous. “Nobody teaches you how to be a leader.”

And, once more, Andy rose to the occasion. “As raw and green as I was, I took over Publicis London. Maybe it’s wild naivety but we created a really strong culture. It was funny, we had a laugh, the work got better and we won awards for the first time in a long time.”

As a creative leader, Andy remembers very well what it’s like to be that inexperienced young creative and so he takes a special interest in giving a hand up to the next generation. “[It] gives me as much pleasure as any award,” he says. “To watch people understand how to cultivate an idea is something I think is really special. It’s our job, in my role, to do that and help that and not criticise them.” He’s under no illusion that it’s always easy to stay open and understanding when you urgently need to get ideas for a client and none are forthcoming. However, he says the key is sitting down and working together with people and taking as much stress out of the situation as possible.

He’s a big believer in giving people space to be adventurous and figure things out their own way. “It’s down to freedom, isn’t it?” he says.

While at Publicis London, Andy’s team created a campaign for the charity The Pilion Trust in which a man attempts to shock people into donating by walking around London wearing a sign that reads: "Fuck the poor."

It’s the job of the creative leader to spot the potential in the half-formed idea, to sift through and find the nuggets as newer creatives are still figuring out how to flex those muscles. “I guess learning to edit your work and know what’s good… that takes a while. I made tons of mistakes, thinking something’s brilliant and I show someone and they go, ‘are you joking?’ You need people around you to help, that’s why I like the studio-based thing where you can show things around,” he explains, reflecting that the individual offices of the ‘80s and ‘90s were perhaps less conducive to that more collaborative way of working.

Which takes us full circle to Le Truc, where it’s all about working collaboratively and freely. Notably, the structure at Le Truc is relatively flat, again an echo of Andy’s early days at BBH. He recalls his naive shock when he first moved to the United States as CCO at Publicis NY where he was confronted by the hierarchy and complexity of agency structures in North America. “I think it’s got better, but when I first arrived there was a lot of hierarchy of creative sign off, which I think is not good for the work. And it’s certainly not good for the morale of the younger team. The less check-ins you can have the better. The worst thing you can have is when you show somebody an idea and then they’ll take it away and show somebody else, and then they’ll take it away and it will come back and somebody’s written all over that. I never had that as a creative because I worked in more flat structures.”

With this flatter structure and greater leeway, Andy’s proud of creating a culture where developing talent can flourish, getting a taste of the adventurous ambition and high standards that shaped Andy as a young creative. “It gives me huge pleasure to see young teams get that opportunity because I think kids come out of college and can get stuck in a rut and sometimes the creativity can almost get drummed out of them when they have to do the same thing over and over and over again. That’s not the case here.”

After 40 years of throwing himself into the unknown, the creativity certainly hasn’t been drummed out of Andy. These days he’s in amongst it, hands on and throwing himself into scary new challenges every day.

“I write all the time, I art direct a lot of the time. I spent probably 13 years as a traditional CCO, where I didn’t have the time to do that. Le Truc has been a gift – for better or worse, I’m back on it. Back on the tools. I love it.”