Change, Chaebol and #MeToo in South Korean Advertising

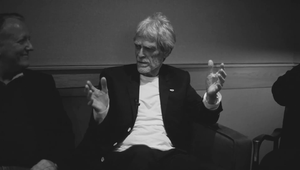

“Where’s the beef?” Sangsoo Chong is frustrated. According to him, excitement, entertainment and emotion have given way to efficiency across the South Korean advertising industry. And his observations carry some weight – the former child actor has been in the industry since the mid-eighties, including a 12-year stint as the ECD and VP at Ogilvy & Mather in Seoul and these days he’s a professor at Cheongju University and the Chairman of the Judging Committee at Ad Stars International Advertising Awards. So he’s got a great vantage point and little to stop him saying it like it is. And there’s a lot to talk about in this evolving and idiosyncratic market.

But if the heat and heart have, in Sangsoo’s opinion, gone out of the South Korean creative, the business competition is hotting up. While the local industry is still dominated by the big four chaebol agencies, and they look set to continue their dominance, there are now over 10,000 companies competing in the market. As a bit of Korean for beginners – chaebol are huge, family-owned conglomerates and the most well-known Korean agency brands are own by chaebol. So Cheil is affiliated with Samsung, Innocean with Hyundai, HSAd with LG and Daehon with Lotte.

Julie Kang is the MD at Serviceplan, one of the non-chaebol agencies jostling in the market for a slice of the huge ad spend. (In 2016, South Korea was ranked sixth in the world for advertising spend, amounting to $11.271 billion.) Following corruption scandals and public pressure, the new President Moon Jae-in has taken a tougher stance on chaebol than his predecessors, explains Julie.

“South Koreans are constantly voicing their opinions on ‘chaebol reform’,” says Julie, who explains that the new government has been vocal about its desire to impose stricter guidelines. “However, since the nation's chaebol system was not formed in a short time, it is expected that it will be difficult to experience any noticeable changes in the early future. It will not be changed easily in a short time, including in the advertising industry.”

But Sangsoo reckons any efforts to date have been insufficient. “The chaebol affiliates still monopolise the advertising volume of their group companies, which mean the situation has not changed. It will never change until the government makes law,” he says.

Youmi Cho, the CEO at Publicis One in South Korea, is somewhat more optimistic. The top five chaebol account for over 50% of the country’s stock market so a slower change might help dampen any shocks. “Big changes will likely not happen any time soon. The Chaebol system has been deeply ingrained into the entire Korean business environment and its influence on the Korean economy is huge. A slower change is not necessarily a bad thing as gradual reform instead of drastic change will help business transition. What is key is that the first step has been taken in the right direction,” she says.

#MeToo

Another area where change is noticeable, though slow, is in the position of women in the industry. As with the rest of the world, the South Korean industry has a paucity of women at the top – though we were lucky enough to talk to two female agency leaders for the piece. In South Korea, Confucian traditions around gender roles and hierarchy make things particularly tough and the overall participation of women in the workplace at all levels is noticeably low – only 53.1% of the country’s women are part of the workforce, compared with 74.5% of men. According to Bloomberg, it’s lower than that of South Korea’s neighbour, Japan.

The current administration, though, is keenly aware that this disparity is an economic vulnerability and has been investing in initiatives to help women return to the workforce after having children and helping women to start their own businesses.

According to Julie at Serviceplan, issues around gender are deeply rooted but for her part, she believes change is happening. “Korea has long been a patrilineal system, culturally based, and as a result of its Confucian background, the culture of seniority and male orientation tend to be spread throughout society,” she explains. “Although the nation is achieving gender equality after much effort, there are still many issues to be solved concerning gender discrimination and the leadership of women in society. However, due to many efforts and attempts, the gap in the percentage of male and female employees in the company has decreased and many women who are ranked high in society are found. It is improving the false perceptions and problems that remain for a more advanced gender equality society.”

The #MeToo movement has been gaining momentum in South Korea, forcing the country to face up to the reality of what women have long had to put up with. There has been a wave of high profile accusations and resignations in the country. One high profile politician stands accused of raping his secretary, while a renowned theatre director has been forced to apologise for abusing his female actors. A slew of claims by students and former students against schoolteachers have also emerged.

“Here, too, it appears a serious problem,” says Sangsoo, who is positively livid about the situation. He notes that in the workplace, this kind of abuse can affect women regardless of whether they have a low status or high status job.

If Sangsoo’s impassioned response is anything to go by, women in Korea are not entirely without male allies. He says that as a father with a daughter, he can well understand a desire for vengeance in cases of assault. “It is not easy to change quickly. But I applaud the courageous young women in Korea... It is time to change a wrong culture [and do it quickly]. Well begun is half done.”

This confluence of government action on maternity rights, pro-active political will to increase the representation of women in the workplace with the visceral truth-telling of #MeToo, represents a watershed.

“The reality is that the number of women in leadership is still very low today but change on this front is happening fast here in Korea and I expect that it will be getting a lot better sooner rather than later. As a woman, I’m really pleased to see this and honoured to be in a leadership position so that girls will grow up accustomed to seeing females as leaders and aspiring female executives will know a leadership role is possible if they choose it.”

Work, Work, Work

South Korea’s ‘economic miracle’, which has seen it go from being one of the world’s poorest countries in the 1960s to a technological powerhouse, has been driven by lots of hard work. Lots. In fact, of all the countries in the OECD, South Korea is second only to Mexico when it comes to the average number of hours worked in a year, coming in at 2,069.

Here, too, the government is taking action and has recently reduced the cap on the maximum number of hours employees can work per week from a whopping 68 to (a still fairly hefty) 52 hours.

“Korean society is famous for its severe working hours due to its rapid development and fierce competition. However, these days, they are moving toward the welfare of their employees rather than focusing only on the work,” says Julie.

And Korean workplaces are changing in other ways. Julie notes that while the vertical hierarchies in South Korean businesses are still pretty prevalent – these structures are credited with driving the country’s huge economic growth over the past half century – some companies are also looking to adopt a more equitable, horizontal model. Indeed, Internet company Kakao is just one of several businesses that make their employees use their English names, to avoid the usual honourifics and tradition of addressing colleagues by their job title in the hopes of achieving a less regimental culture.

So if all those regimented hierarchies that have long provided the scaffolding for South Korea’s business culture are slowly – very slowly – being chipped away, perhaps Korea’s creative souls will find more space to spread their wings. Change does not happen overnight, but on the other hand South Korea is a country with a track record of forcing through massive social and economic change if it really wants to. If these aforementioned changes do come to fruition we could see a very different advertising industry. If chaebol reforms make space for start ups, women start taking the reins of leadership, non-frazzled workers find themselves with a bit of headspace… maybe Sangsoo might find some of that ‘beef’ that he’s looking for?